It’s a feather in the cap for all GM truck fans that General Motors produced one of the most historically important trucks in existence. The 1940 GM Futurliner No. 10 had the honor of being the very first truck (and only the sixth vehicle overall) to be added to the National Historic Vehicle Register. That was back in 2015, so this is admittedly old news—but isn’t that what history is all about?

Futurliner No. 10 made headlines at the time of that announcement from the Historic Vehicle Association (HVA). Yet many people still don’t know what drove GM to create one of the most objectively cool trucks ever, or how the Futurliner managed to symbolize the very latest thing for a full 15 years.

It all started with the Parade of Progress, more than 80 years ago.

The Parade of Progress was first conceived by GM Research Director Charles F Kettering (aka “Boss Ket”) in 1936. Seeing how the company’s elaborate “Science and Technology” display at the Chicago World’s Fair worked to cheer a Depression-weary populace, Kettering was inspired to take the show on the road.

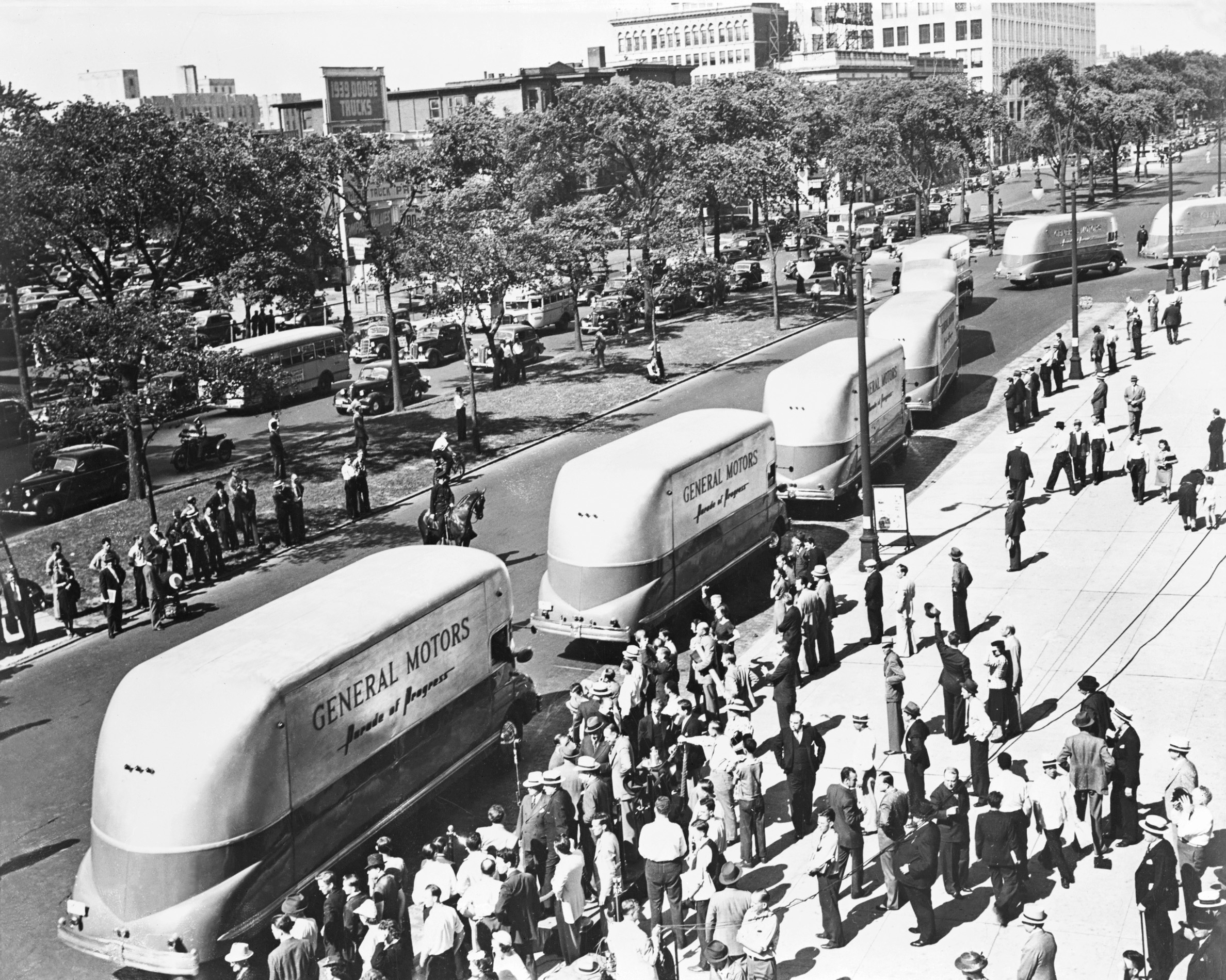

For that first run, GM built 8 “Streamliner” vans, which toured the country with a caravan of smaller trucks and other vehicles for three years. The Parade was a great success, so for its second iteration, which debuted at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, GM really went all out. They recruited the Yellow Truck & Bus Division and Fisher Body to create 12 vehicles, dubbed “Futurliners,” that would run the show.

Purpose-built and hand-crafted, the Futurliners are like nothing that came before or since. They were streamlined (if such a term can be applied to an 11.5-foot-tall rolling wall) like their predecessors and styled by famed GM designer Harley Earl. Earl’s signature liberal amounts of chrome accompanied a striking red-and-white paint scheme that was topped off with a glass bubble of a cockpit (which later had to be redesigned to avoid baking the driver).

The center cockpit looks futuristic even by today’s standards, but the innovation didn’t end there. The Futurliners featured dual front and rear wheels, for a total of eight. Each truck was 33 feet long, 8 feet wide, and weighed 12 tons. The inline-six GMC engine not only powered the massive vehicle across the country but also fueled the generator that allowed its many features to be used, as each was outfitted with all the bells and whistles needed to really put on a show.

The 16-foot panels on either side of each truck folded up and down to create a kind of covered stage a few feet off the ground. A roof panel hid the lighting tower, which extended straight up to reveal a bank of flood lights, and each truck had its own public address system. Each Futurliner was essentially a rolling theater, complete with marquee: the contact point of the top side panel, when exposed, featured the title of the exhibit contained within.

The Parade was meant as a nation-wide pick-me-up, never a money-maker, and the exhibits the Futurliners hosted brought a vision of a bright new future to small-town America. The convoy moved with the seasons, traveling year-round to bring this spectacle of edutainment to millions.

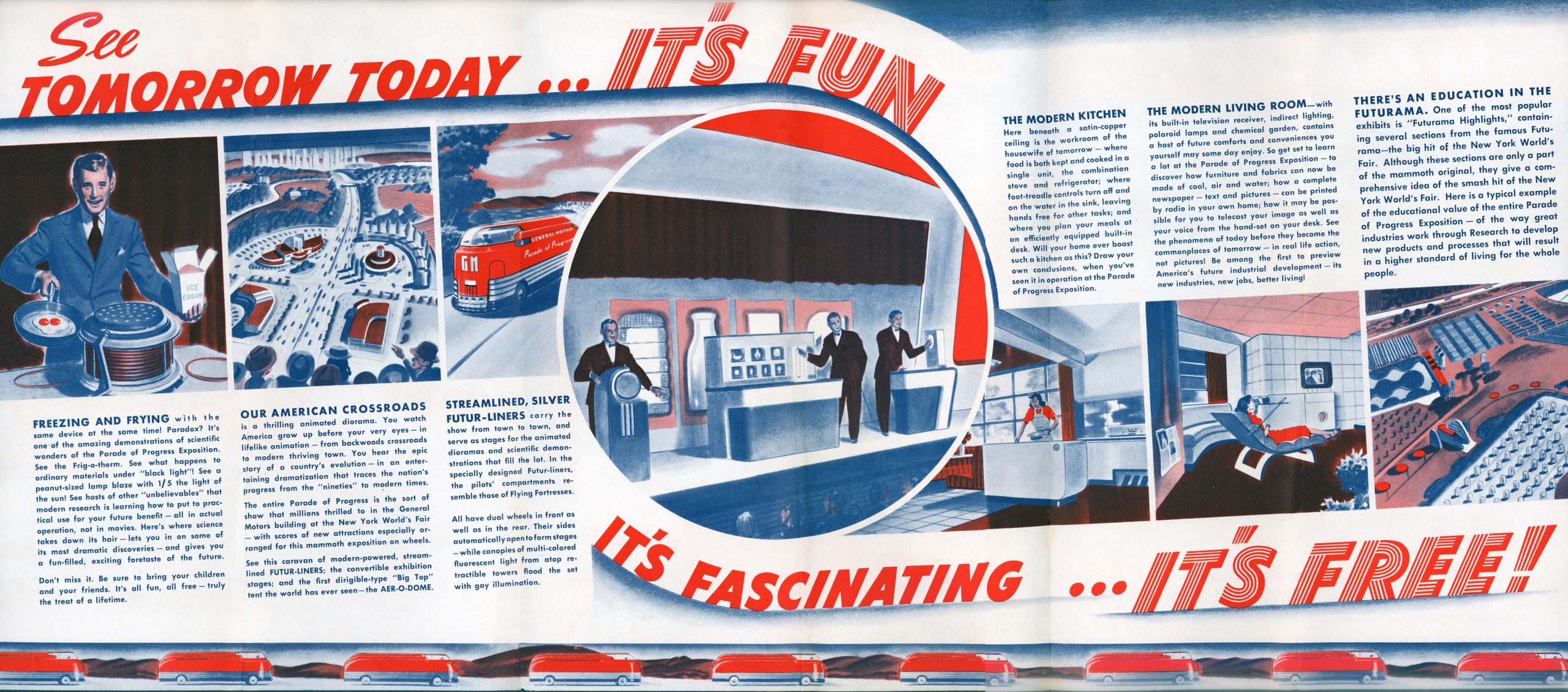

“See tomorrow today!” blared the 1953 brochure. “It’s fun . . . it’s fascinating . . . it’s free!”

Fascinating it was, and is. These days, scientific advances are so abundant that they rarely break into mainstream news. The inventory of innovations that were considered worth showcasing paints a picture of a period defined by optimism and expansion.

GM had plans for air travel, rail travel, and highways. The company wanted to be in your kitchen, your living room, and your driveway. It wanted to free America’s mothers from “domestic drudgery” with efficient new kitchens and inspire America’s youth (or at least its boys) with soap box derby displays and whiz-bang science demonstrations.

Supporting vehicles—44 in all—made up the rest of this convoy of convoluted creations, but the Futurliners were the stars of the show. Though other vehicles were cycled in and out, the Futurliners remained pivotal until the Parade’s end, and they were revamped rather than replaced when the show returned after a hiatus for World War II. The Futurliner was evidently considered modern enough to retain its name and central role for nearly 15 years.

The Parade concluded in 1954 due to waning attendance (caused in part by the rising popularity of television, one of the very innovations the Parade had showcased). General Motors retained just one of the 26 exhibits, the animatronic “Our American Crossroads,” which still runs at the GM Heritage Center today. Everything else was disassembled, and the fleet of Futurliners was split up.

Eleven survived at that time (one had been destroyed in an accident). Two were gifted to the Michigan State Police and became “Safetyliners.” Others were sold off and began new careers hawking beer (for Goebel Brewing), Cadillacs (for a Detroit-area dealership), or gospel (for Oral Roberts). Changing hands and enduring long periods of outdoor storage over the intervening decades, several Futurliners have gone missing.

Hemmings is tracking the Futurliners as they change hands and periodically updating Daniel Strohl’s 2013 article with news. Here’s what we know for sure:

No. 3, which carried the “Power for the Air Age” exhibit, was restored by Kindig-it Design of Utah. The 22-month restoration brought the entire outfit back to its former glory, right down to the Allison J-35 jet engine it was built to display.

Two Futurliners now belong to the Peter Pan Bus Company of Springfield, MA. One, believed to be No. 6 (“Energy & Man”), was fully restored and is displayed regularly; the other, unidentified, is kept to serve as a donor truck should anything happen to its sister.

ChromeCars in Germany has acquired at least three over the years, thought to be Nos. 5 (“World of Science”), 7 (“Out of the City Muddle”), and 9 (which served as the Parade’s reception center).

And, of course, No. 10 landed on the HVA Register. Concept car collector Joe Bortz rescued No. 10 and four other Futurliners in the 80’s from a fellow restaurateur who planned to chop the trucks up for eatery décor. Bortz donated No. 10 to the National Automotive and Truck Museum in Auburn, IN, where it was lovingly restored at great expense (the custom-made white wall tires alone cost $10,000) by a team of volunteers. Displayed where many can enjoy it, No. 10 continues to live out its original purpose, bringing joy to the masses. It even travels from time to time.

GM’s 12 Futurliners were a symbol of America’s progress and potential for over a decade. They’re an important part of GM’s history and no doubt responsible for a good deal of its present as well.